The phrase “great minds think alike” has been attributed to many people, and it’s possible some of these people were unaware of its utterance elsewhere. Some now believe it dates back to 1618 with the phrase “good wits doe jumpe” by playwright Daubridgcourt Belchier, where “jumpe” here means “coincide.”

In 1922, Political Science Quarterly published “Are Inventions Inevitable? A Note on Social Evolution” by American sociologists William F. Ogburn and Dorothy S. Thomas. Their paper argues that inventions are largely inevitable when one takes into consideration the knowledge and needs that steer innovation, inventions are largely unavoidable, suggesting that many inventions were going to happen anyway, despite who invented them, given that the necessary conditions were present.

They begin by saying, “many of these inventions have been made two or more times by different inventors, each working without knowledge of the other’s research” then list several well-known as well as little-known examples: Newton and Leibnitz invented calculus; Wallace and Darwin each developed the theory of natural selection; Langley and Wright invented the airplane; Gray and Bell invented the telephone; photography was invented by Daguerre and Talbot; oxygen was discovered by Scheele and by Priestley in 1774; and more.

Robert K. Merton cites this work in his 1963 essay “Multiple Discoveries as Strategic Research Site” where he develops his multiple discovery model or “Merton’s models” and the phenomenon of discoveries being independently made by scientists unaware of each other’s work (not to be confused with economist Robert C. Merton, who developed his own “Merton model,” a multiperiod model of assessing financial risk in 1974):

”Sometimes the discoveries are simultaneous or almost so; sometimes a scientist will make a discovery which, unknown to him, somebody else had made years before.

Another example is the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics, which proposes the idea that at every junction where everyday things interact with the quantum system (a composite system generated from different quantum states), the timeline of history splits and possibilities happen on different alternate branches. These alternate universes are completely separate and unable to intersect. American physicist Hugh Everett came up with this idea in 1955, not realizing Erwin Schrödinger had basically the same idea five years earlier.

The similar string theory, originally developed in the 1960s and early 1970s, suggests many universes exist parallel to each other and can potentially intersect. While these intersections might be presumably unnoticeable, perhaps it’s enough time for one idea from a separate universe to travel into another.

In the world of entertainment, the phenomenon seems more accountable, like the “twin films” phenomenon. For example, meteor disaster films Touchstone’s Armageddon and DreamWorks’ Deep Impact were released around the same time, as were two big budget animated insect films, DreamWorks’ Antz and Pixar’s A Bug’s Life. All four were released in 1998 with the same two larger studios in competition at the box office.

Lesser-known examples include Hal Ashby’s Being There and Carl Reiner’s The Jerk released one week from each other in 1979, both films are about witless fools who are catapulted to fame and success. In 1956, Nicholas Ray’s Bigger Than Life and Robert Aldrich’s Autumn Leaves were both psychological melodramas dealing with mental illness and just happened to have been released a day apart. Often, studios are aware of what each other is producing.

In the second half of 1968, pop-rock groups the Byrds and the Everly Brothers both released albums, Sweetheart of the Rodeo and Roots, respectively, representing their forays into country music.

In the mid-70s, Roberta Flack and Bad Company released separate songs titled “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” In 1971, the Carpenters and Murray Head released different songs with the title “Superstar.”

In the last year and a half, Authors Erin Cotter and Jodi Picoult released books with the title By Any Other Name within months of each other.

Wrestler Steve Borden changed his ring name from Flash to Sting in 1986, the same year the pop-rock band the Police broke up and its lead vocalist, Sting, would continue his solo career.

Great minds, etc.

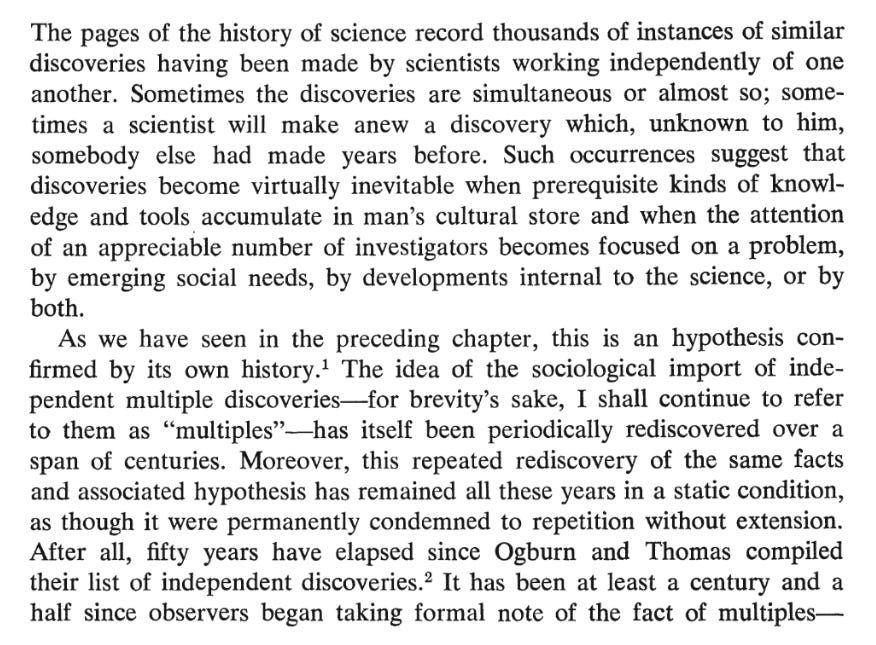

Recently, this photo of George Harrison on the set of the Traveling Wilburys’ 1988 music video “Handle with Care” popped up again on one of my social media timelines. This time I saw it, though, I was compelled to find out who or what is on Harrison’s t-shirt.

Google Lens and Images didn’t help me even after finding another clearer photo from the same set but from a different angle where the image on the shirt appears to be animated characters.

Since the video was shot and released in 1988, I searched “British animated characters 1980s” and found the below image, which I presumed were different illustrations of the same characters.

Lens and Images actually did help me this time and I learned these are the title characters from a 2017 British animated series Dennis and Gnasher. Then, I soon found the below image of the same t-shirt Harrison was wearing in the photos and music video. (“Menaces For Ever” as it reads on the shirt could very well have been Harrison’s personal hidden joke slogan for the Wilburys themselves.)

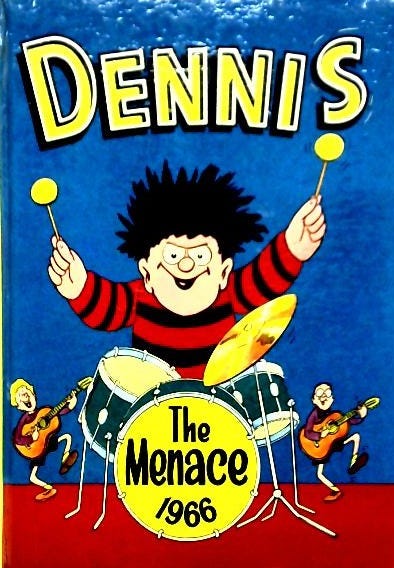

Dennis and Gnasher are characters featured in the British comic strip Dennis the Menace, which debuted in the UK weekly reader The Beano. a British anthology comic magazine first published in 1938 and created by Scottish publishing company DC Thomson, based in Dundee, Scotland. As an American, I wasn’t as aware of these characters, may have heard about them in passing, but they are apparently entrenched in British culture.

(I was informed Harrison’s longtime pal and semi-frequent collaborator, Eric Clapton, is reading The Beano on the cover photo of the John Mayall with Eric Clapton album Blues Breakers, which is colloquially known as The Beano Album.)

This Dennis was born when The Beano wanted a new strip, and one of the editors, either George Moonie or Ian Chisholm, had recently heard the music hall song “Dennis the Menace in Venice” and thought Dennis the Menace would be a great title for said strip. Chisolm recruited artist Davey Law to create the character. Chisholm wasn’t happy with Law’s early ideas and ended up sketching the design, giving Dennis a scowl and spiky hair. Law would continue to draw the strip. Dennis’ trademark hound, Gnasher, was added in 1968.

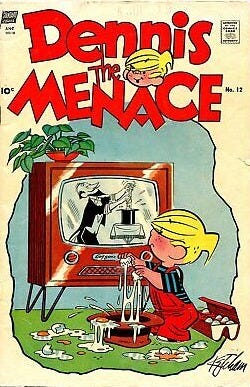

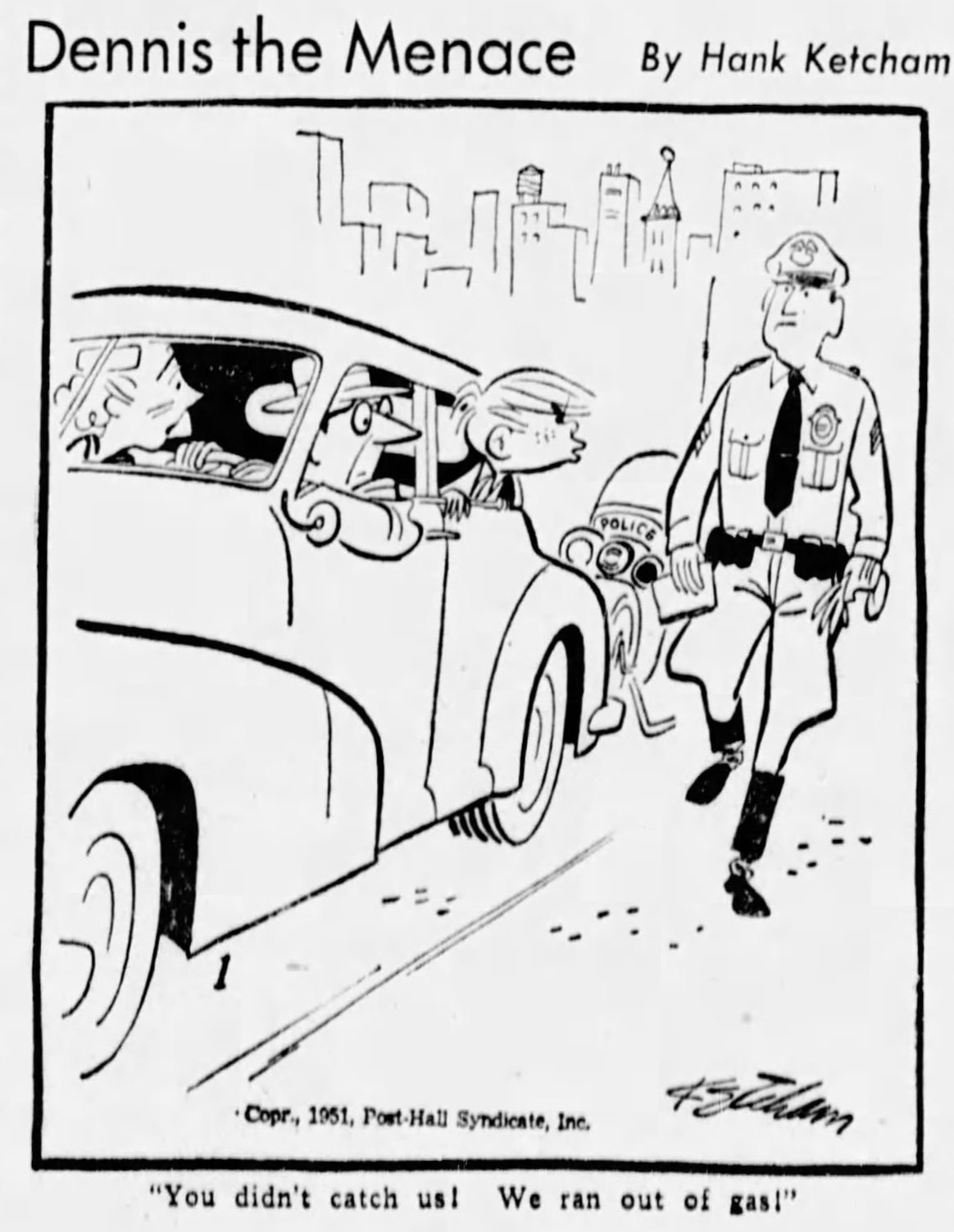

Meanwhile in the United States, cartoonist Hank Ketcham was working as a freelance cartoonist in Carmel, California. He had been assistant animator for Walt Disney, where he worked on Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi, and several Donald Duck shorts. During World War II, he created the character Mr. Hook for the Navy, and four cartoons were made—one by Walter Lantz Productions, in color, and three by Warner Bros. Cartoons, in black and white.

He created Dennis the Menace based on his own four-year-old son Dennis. Ketcham has said in the fall of 1950 his first wife, Alice, stormed into his studio and complained that their four-year-old, Dennis, had wrecked his bedroom instead of napping, shouting, “Your son is a menace!” Ketcham’s strip would debut in a few months.

Of this Dennis, I was keenly aware. I read the strip often as a kid and I have one of my dad’s childhood Dennis the Menace paperback collections from the 1960s that’s slowly disintegrating.

Two different comic strips sharing the same name were born in two different continents by creators—one by an American cartoonist, the other by Scottish editors and cartoonists—unaware of what the other was doing, unaware of the other strip’s inception and development.

The similarities mostly begin and end there. The American Dennis is published in England under the title Just Dennis, while the English strip is published internationally as Dennis and Gnasher.

In the 2016 Smithsonian Magazine article “Dennis the Menace Has an Evil British Twin,” James Parker writes:

“Mischief was the common concept: Both Dennises were rowdy boys, running amok, turning the grown-up world on its head. American Dennis was a little tearaway in dungarees, an adorable scamp pestering poor Mr. Wilson next door. He did and said the darnedest things; you couldn’t stay mad at American Dennis. British Dennis was much further along the mischief spectrum—a disturbed maverick of prepubescence, a bully, a nemesis, a persecutor of “softies” (in particular the unfortunately recurring Walter), a mean-minded vandal with whom the authorities were in a permanent and justified rage.”

Both Dennises have also been seen with slingshots. Both Dennises were published in several paperback collections. Both Dennises have been adapted into other mediums.

But the most jaw-dropping similarity would have likely intrigued the multiple discovery model sociologists, or at least had their attention:

While the date listed on the issue of The Beano is March 17, 1951, the issue was on sale on Monday, March 12, 1951, the same day Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace debuted in sixteen newspapers in the United States.

Again, the creators of these strips that share the same name and theme of mischief were unaware of the other’s creation, much less publication date.

Psychiatrist and evolutionary theorist Carl Jung would define synchronicities like these as “meaningful coincidences that cannot be explained by cause and effect.” That is, they are not just random occurrences, but rather manifestations of a deeper order in the universe, or connections to the collective unconscious.

Maybe the conditions were such that the inventions were inevitable.

Or maybe parallel universes intersected.

The parallel comic strips, after all, are still running.

Or maybe simply, good wits doe jumpe.