Leave 'Em Wanting Lore

Fiction for consumerism

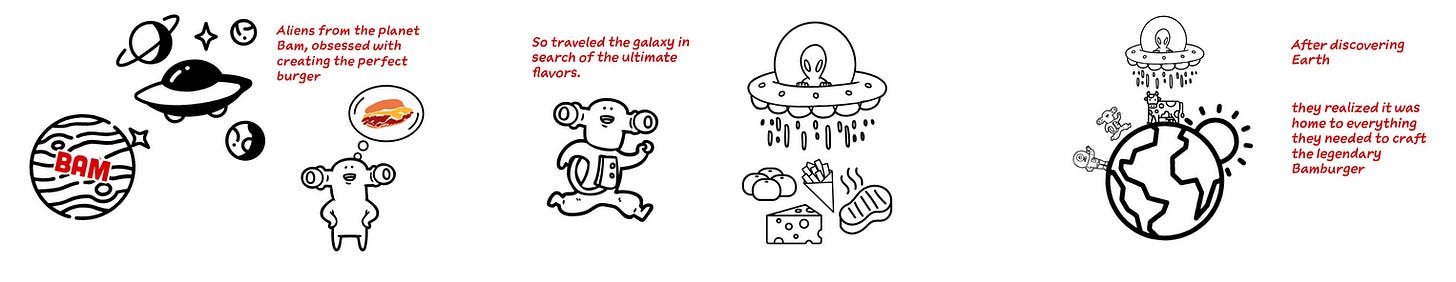

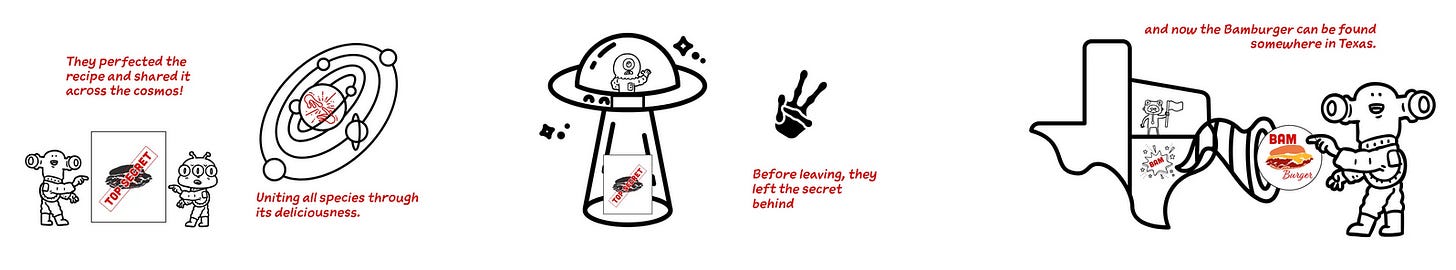

Over the weekend, a friend posted a series of photos to his Instagram Stories from his visit to the restaurant Bamburger located in Spring, Texas. He prefaced the photos with the text: “Incredible burger lore drop coming.”

What followed were pics of sequential illustrations posted in the store that tell a lighthearted comic book tale of how Bamburger came to be. Aliens from the planet Bam, consumed with creating the perfect burger, journeyed through the galaxy in search of the best flavors, and discovered Earth had everything they needed. They perfected the recipe, shared it across the universe, and united all species before leaving behind the secret on Earth where the Bamburger can now be enjoyed in Texas.

The use of a fictitious backstory for marketing purposes to sell products is nothing new. (Contemporary online vernacular has traded “backstory” for the more comic book-y “origin story” to the now-trendy “lore.” That said, “lore” and sometimes “origin story” can also apply to one’s non-fictional history, vague auto-fiction, gossip, myth, and apocrypha.)

The brand history of Hollister, a subsidiary of Abercrombie & Fitch focusing on surf wear and Southern California-inspired clothing, centers on “founder” John M. Hollister, who graduated from Yale in 1915 with a yearning for adventure, leaving the New York establishment for the Dutch East Indies (which later became Indonesia) where he bought a rubber plantation and fell in love with Meta, the daughter of the plantation’s previous owner. He sold the land soon afterward, bought a schooner, sailed the South Pacific with Meta, and settled in Los Angeles where he and Meta married and had a son, John M. Hollister Jr. Hollister Sr. founded Hollister Co. in Laguna Beach in 1922 as a trading company selling imported goods from the South Pacific. John Jr. became a legendary surfer, took over the business in the 1950s, and expanded it to include surf apparel and gear.

While the company’s story reflects a love of adventure, the ocean, and romance, it is an entire fiction. Hollister didn’t open in Laguna Beach in 1922 but in Columbus, Ohio, in 2000 (at the same Easton Town Center featured in one of my first posts). The fictitious history was an idea created by then-Abercrombie CEO Mike Jeffries to generate a fake authenticity for the company.

Both Gilly and Fitch and Ruehl No. 925, two other Abercrombie subsidiaries, were also lent fictitious lore under Jeffries’ tenure. For the former, Gilly Hicks was a liberated Englishwoman who moved to Australia in the 1930s with her granddaughter, who later in life returned to her grandmother’s historic Sydney manor house to set up a contemporary lingerie store. In actuality, the first store opened in Natick, Massachusetts on January 21, 2008.

Five years later, Abercrombie & Fitch announced it would close Gilly Hicks' retail stores, though its products are sold online and in all Hollister stores.

According to Ruehl No. 925’s backstory, the company takes its name from the Ruehl family, who moved from Germany in the mid-1800's and opened a leather goods emporium at 925 Greenwich Street in Manhattan with Abercrombie buying the rights to the name from the family in 2002.

Although the labels on all the clothes read “Ruehl No. 925 Greenwich Street, New York, NY,” there was no Ruehl family. Also, there is no Ruehl store in New York City, nor a 925 Greenwich Street. The first Ruehl No. 925 stores opened on September 24, 2004 in Paramus, New Jersey, Schaumburg, Illinois, and in Tampa, Florida.

Five years later, Abercrombie & Fitch announced it would close its Ruehl division because of the recession.

As part of a Twix candy bar Left Twix vs. Right Twix promotional campaign, the company released a fictional history involving two brothers, Seamus and Earl, who in the fall of 1920 wanted to create a new candy bar that was the perfect blend of cookie, caramel, and chocolate. However, as they worked toward their dream, they disagreed on nearly everything. A rift developed between them, and they went their separate ways. They built their factories side-by-side and belittled each other’s operations. Left Twix created “a crunchy cookie with caramel flowing over it, followed by a bathing in chocolate,” while Right Twix opted for a “crisp cookie base with caramel cascaded over it and cloaked in chocolate.” The brothers failed to reconcile, and a right Twix and a left Twix would never be packaged together, asking customers to choose between the two.

The Left Twix vs. Right Twix campaign was a 2014 finalist for the distinguished Effie advertising award.

Though most of us associate the Betty Crocker brand with its products, the idea and name arrived much earlier. The brand isn’t a namesake for a real person, nor is there a faux origin story. Instead, a fictitious personality developed with momentum.

In 1921, the Washburn-Crosby Company sponsored a contest for home cooks to solve a jigsaw puzzle for the chance to win a pincushion in the shape of a bag of Gold Medal Flour. Washburn, a flour-milling company and predecessor of General Mills, Inc., was shocked to find themselves overwhelmed with questions from home cooks who used the contest as an opportunity to ask for expert baking advice.

The company’s advertising department convinced its board of directors to devise a character and signature for responses to the letters. The surname Crocker was chosen in honor of a retired executive from the company and “Betty” simply sounded friendly. Washburn-Crosby asked their female employees to try their hand at a Betty Crocker signature. Florence Lindberg’s was chosen and has been used—or variations of it—for over a century.

Three years later, The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air, the first cooking radio show, debuted in Minneapolis in 1924. A national show debuted in 1926 and lasted until 1953 with different woman voicing the Betty Crocker character, one of whom was Marjorie Husted, who over decades helped Washburn-Crosby/General Mills develop the idea into an empire.

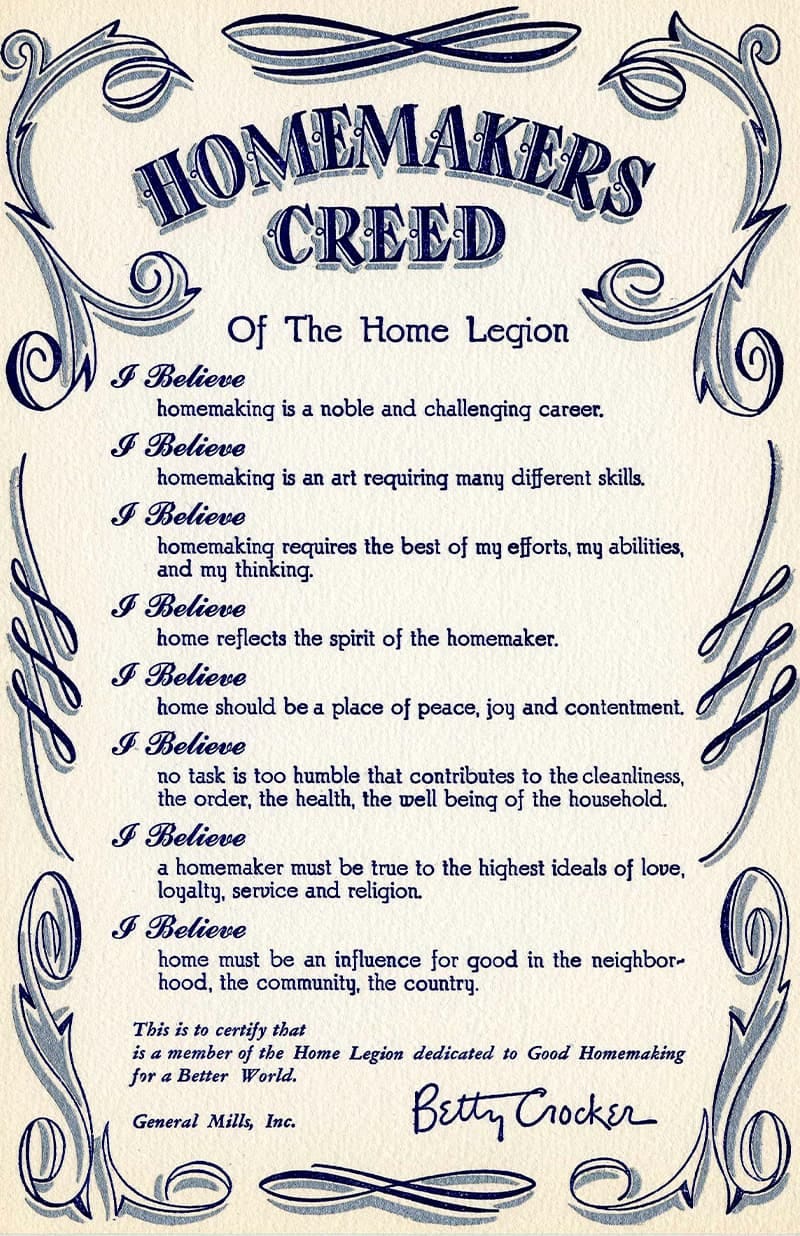

In 1950, the first Betty Crocker hardcover recipe cookbook was published. A year later, television show debuted. More cookbooks, test kitchens, and, of course, products followed. There was even a Home Makers Creed slipped into some early cookbooks and signed by Betty Crocker. The fiction had then developed into a religious-like set of values. Betty Crocker not only became an idea of a person but of a way of life.

The origin of the soft drink brand Dr. Pepper has been a subject of some debate and a continued mystery, yielding multiple stories and an unknown truth. There was indeed a Dr. Charles Pepper of Rural Retreat, Virginia, who is also buried there, and he’s believed to be the namesake of the drink. Beyond that, however, reality and myth begin to obscure. Pepper had hired a young pharmacist named Wade Morrison, who later moved to Waco, Texas, to open his own drugstore and sell the drink there (Waco is also where the Dr. Pepper Museum is located). Charles Alderton is generally credited for inventing the drink and then giving it to Morrison to sell at his Waco drugstore.

According to some stories, Morrison was in love with Pepper’s (possibly underage) daughter and named the drink for the doctor in hopes of winning his approval (and subsequently run out of town, if the underage part is true, hence, his move to Waco). Another is that it was simply Morrison’s way of thanking Pepper for giving him his first job. Some Rural Retreat locals claim that Morrison merely mass-produced a fizzy drink made of herbs and roots originally concocted by Pepper rather than by Alderton later in Waco. Others believe that the name Dr. Pepper was chosen to bolster early marketing claims that the drink was an energizing brain tonic.

The drink was first used commercially in 1855. Dr. Charles Pepper died in 1903. His obituary mentions nothing of the drink.

As opposed to an ad agency or department creation, most of these myths likely developed through gossip, and local boasting including a Rural Retreat vs. Waco point of pride, with a kernel of truth at the heart of all of them. And unlike the others, Dr. Pepper hasn’t really used any of its (debatable) backstory to sell its product to the public. It just exists.

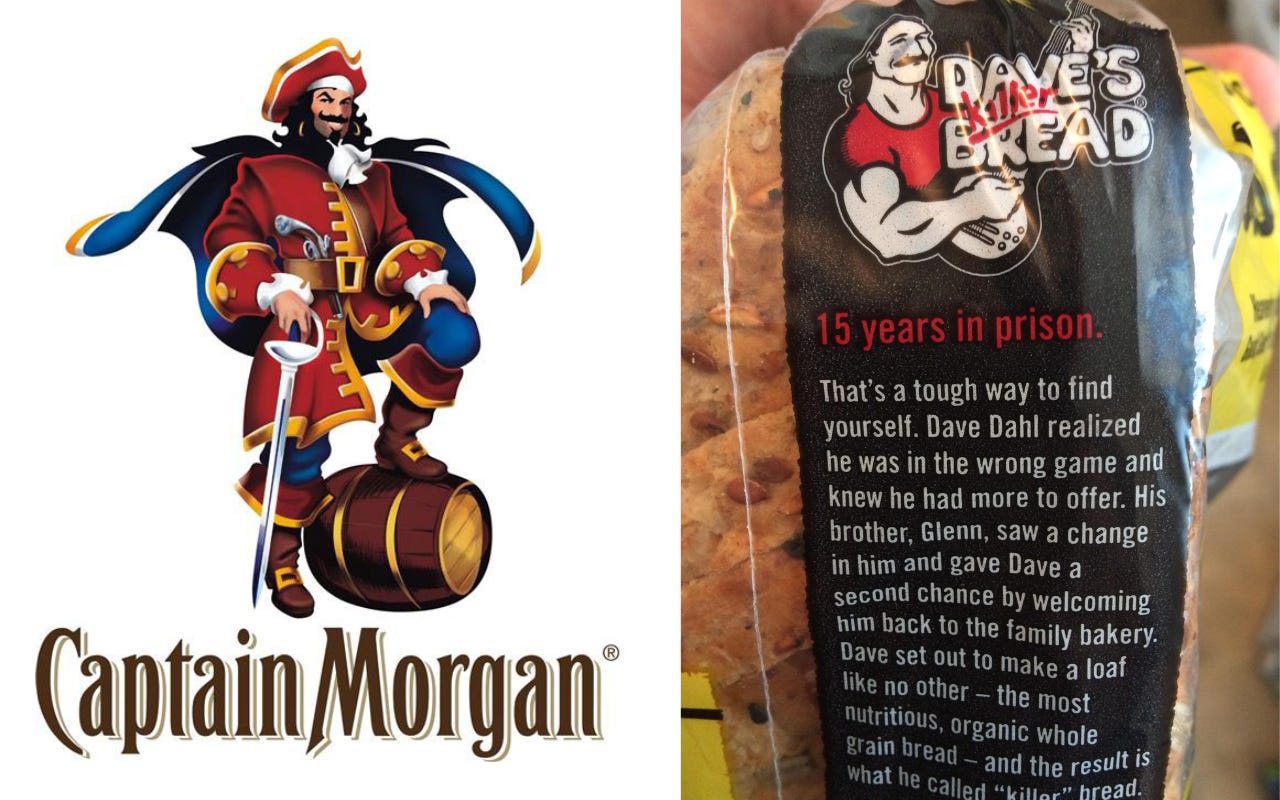

Captain Morgan brand rum is named after the 17th century Welsh privateer—or buccaneer, marauder, raider, pirate—Henry Morgan. The branding has labeled him a “buccaneer” and that the rum has been “crafted in honor of the Captain’s legendary private reserves.” It also said that he was “a natural born leader, his great charm won him the respect of nobleman and the loyalty of his crew.”

What it hasn’t mentioned is the Captain’s invasion of Panama in 1671 with rape, murder, pillage, ransom, torture, theft, and betrayal of his fellow pirates all included. For the cost of 15 men, Morgan had killed or wounded 450 Spanish and succeeded in capturing Panama City. Fearing retaliation from Peru or Colombia, he escaped Panama with most of the loot, leaving his fellow pirates behind, but returned to Central America three years later and was named lieutenant governor of Jamaica, serving as active governor from 1680 to 1682. He died wealthy.

The rum’s Morgan lore is presented with enough actualities sanded off to make it a near-fiction. A whitewashing. A fractional distillation, if you will. Like teaching Christopher Columbus to elementary schoolers. Lying by omission, as some would call it.

Then there’s Dave’s Killer Bread where the lore is nonfiction, but almost sounds like a darker Abercrombie & Fitch-composed fiction. The wrapping on a loaf of bread is branded with a very general peek at Dave’s story:

“15 years in prison. That's a tough way to find yourself. Dave Dahl realized he was in the wrong game and knew he had more to offer. His brother, Glenn, saw a change in him and gave Dave a second chance by welcoming him back to the family bakery. Dave set out to make a loaf like no other—the most nutritious, organic whole grain bread—and the result is what he called ‘killer’ bread. Dave's Killer Bread® is built on the belief that everyone is capable of greatness. What began as one man's journey has turned into so much more. Today, one third of the employees at our Oregon bakery have a criminal background, and we have witnessed first-hand how stable employment sparks personal transformation.”

More specifically, Dave grew distant from his family, indulged in alcohol and drugs, then started committing multiple robberies (one was stealing a $12.99 phone accessory, which landed him in jail), and four subsequent prison sentences (he woke up in jail the morning of his junior year finals) with his final sentence being for assault, possession and delivery/manufacture of a controlled substance. The crimes and sentences all began to blur together.

When he was 38, suicidal, and looking for answers, he sought help and was prescribed antidepressants. Things started “working better,” he said. He learned to play guitar and when he got out in 2004, he started working in his brother’s bakery. He eventually believed he could make better healthier loaves of bread and the rest is history.

You may think, “I’m surprised that hasn’t been a movie.” I thought that, too, particularly with the recent trend over the last decade and a half of feature films about the creations of companies and products (The Social Network, Blackberry, Air, or Flamin’ Hot about the origin of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos which went on to earn an Oscar nomination). Sure enough, according to Dave himself, his story is expected to be the subject of both a documentary and feature film, the latter possibly starring David Harbour (Stranger Things).

These kinds of feature films run all over the fact-fiction spectrum. Where the aspects of the true story are then fictionalized for the purposes of feature storytelling—taking creative license. Books and movies are different forms from each other as are nonfiction backstories and their adaptations. So, ultimately, Dave’s Killer Bread could have a partly true/partly fictionalized commodified tale released into the world. The brand-and-fiction ballet dances on.

Last month, the sandwich chain Jimmy John’s released a “smut audiobook” narrated by actor Walton Goggins (White Lotus, The Righteous Gemstones). Entitled The Blade and the Brine, the two-part “romantasy audiobook” was available for the chain’s Freaky Fast Rewards members who purchased any sandwich or wrap between June 23 and July 6 (sorry if you missed it). The book was part of its Summer Menu of Ultimate Temptation, or S.M.U.T., campaign of new menu items—so, here we have a promotion of literal fiction as an incentive for consuming.

It’s only a matter of time, if it hasn’t happened yet or already in the works, before a restaurant or retail franchise develops a fictional lore-based binge-able streaming series. Perhaps you’ll find it on, say, Chick-fil-A’s streaming service.

Is this simply capitalism, the near-constant human need for made-up stories and characters, or both? Lore is context and fiction is fantasy, both supportive tools for selling things to people, and sometimes those creations take on a life of their own. Fiction, like Betty Crocker’s creed, becomes a tool to not just sell a product but also, again, ideals. Looking at the Creed above is not unlike looking at the Ten Commandments.

The fiction-and-consumerism-as-bedfellows concept has been ingrained in the culture for a long time. It’s who we are. Restaurant mascots as toys or comic book characters, lores behind ad-created characters, characters portrayed in a series of TV commercials, characters performed on radio to sell flour and create what we know as country music. Grandpa Jones is a character. Minnie Pearl is a character. Ronald McDonald House is a charity providing temporary housing for families of seriously ill children who are receiving medical treatment at nearby hospitals, and named after a clown character who was created to promote a hamburger chain. (We’ve already explored here naming towns after consumerist entities.)

Is it really any different for a company to use a lore to market and sell their product than it is for us to watch a fictional television show with commercial breaks? Actor Jim Varney co-created Ernest P. Worrell for local TV ads that became so popular the character was then featured in ten films and a Saturday morning TV series. Wouldn’t a film about the computer animated M&M characters be similar enough to an Alvin & the Chipmunks animated film, or Toy Story? Look at the Barbie phenomenon two years ago. And aren’t films, shows, even books products themselves? It all obscures and cross-pollinates with each other, all creative acts with slightly different endgames with many feeding off each other. The Jimmy John’s book The Blade and the Brine may be a head-scratcher to some, but dig around the internet a bit and you might find fan-made erotica featuring Flo from Progressive Insurance.

The play is the thing: juxtaposition and manipulation.

Speaking of Abercrombie & Fitch, former CEO Jeffries, the one who created those imaginative backstories behind a few of their companies, has been in the news recently for being currently deemed unfit to stand trial for a sex trafficking and prostitution indictment due to dementia. Confabulation, commonly seen in patients with dementia, is the spontaneous production of false memories, blurring the line between reality and fantasy. The victims’ lawyer questioned the timing of Jeffries’ diagnosis, suspicious it was possibly another Jeffries fiction.

So strange. Lol