Mabel's Bonfire

Mabel Riddel and postwar comic book burnings

A local friend of mine recently posted online a passage from Susan Orlean’s 2018 non-fiction book The Library Book, about the unsolved 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library, which reads:

“There have been a number of book burnings in the United States, mostly as statements of outrage over the content of the books. In the 1940s, for instance, a West Virginia schoolteacher named Mabel Riddle, with the support of the Catholic Church, began a campaign to collect and burn comic books because of their enthusiastic portrayal of crime and sex. The bonfire, which consumed several comics, was so warmly received that the idea spread to towns across the country, and many local parishes sponsored their own comic-book fires. In a few instances, nuns lit the first match.”

As a lifelong West Virginian, this was actually the first I had heard of Mabel and her bonfire. Where in the state did this happen? What year in the 1940s? Support from the Catholic Church in what ways? What else is there to know about Mabel Riddle? Et cetera.

After several searches, however, I didn’t turn up much about her at all. I found this WVU Libraries blog post referencing the same mention in Orlean’s book, writing:

“Orlean discussed book burnings of other kinds and the one that really grabbed me was the burning of comic books in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia, instigated by a schoolteacher, Mabel Riddle, in the 1940s.”

The Orlean passage doesn’t mention Spencer, specifically (unless it’s elsewhere in the book), but from there I came upon the teacher’s grave information online and discovered her surname was spelled “Riddel” rather than “Riddle” as it’s spelled in Orlean’s book.

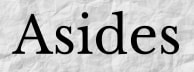

A photo and caption in the October 27, 1948, edition of the Charleston Daily Mail (today, Charleston is approximately an hour from Spencer) reported six hundred Spencer grade school students attended the burning of “2,000 comic books after weeks of collecting them and David Mace, 13, who officiated, said the pupils had made a pledge to quit reading the books.”

Mace continued to say how harmful comic books were to young readers being “mentally, physically, and morally injurious to young boys and girls.”

Mace was part of a campaign instigated by the Parent Teacher Association after Riddel told the group the books had an “evil effect on the minds of young children.”

According to David Hajdu’s 2008 book The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America (read pages 114-119 for the Spencer, WV content), Mace said he bought and enjoyed comic books up until eighth grade when one day Riddle, who was one of his teachers, asked him to stay after class.

She sat next to him in a student desk and told him what she had told the PTA: comic books have an “evil effect” on young minds. She asked him to lead other students in a revolt against comics.

“She was extremely dedicated,” said Mace. “The things she had to say made a lot of sense. I could see that, and she told me we could do something about it, and I said ‘Well, let’s go!’”

For nearly a month, he led several dozen students on a door-to-door hunt through town collecting comics from homes and stores, putting them in milk crates and wagons.

At the bonfire on Tuesday, October 26, 1948, the books were put into a pile said to be six feet high. Six hundred students formed a semicircle around it. Master of ceremonies Mace led the students in a ritualistic call-and-response:

“‘Do you, fellow students, believe that comic books have caused the downfall of many youthful readers?’”

In unison: ‘We do.’

‘Do you believe that you will benefit by refusing to indulge in comic book reading?’

‘We do.’

‘Then let us commit them to the flames.’

With that, according to Hajdu, “he walked a few steps to the pile, took a matchbook from a pants pocket, and lit the cover of a Superman comic… Mrs. Riddel stared with her arms crossed. Several children wept—a signal to those who noticed that not everyone in town agreed with everything that went on in Spencer that day.”

This was not the first reported comic book burning in the United States. According to an August 12, 2014, article in Lapham’s Quarterly by Jacqui Shine, the first reported event happened in Wisconsin in November 1945, but received little national press:

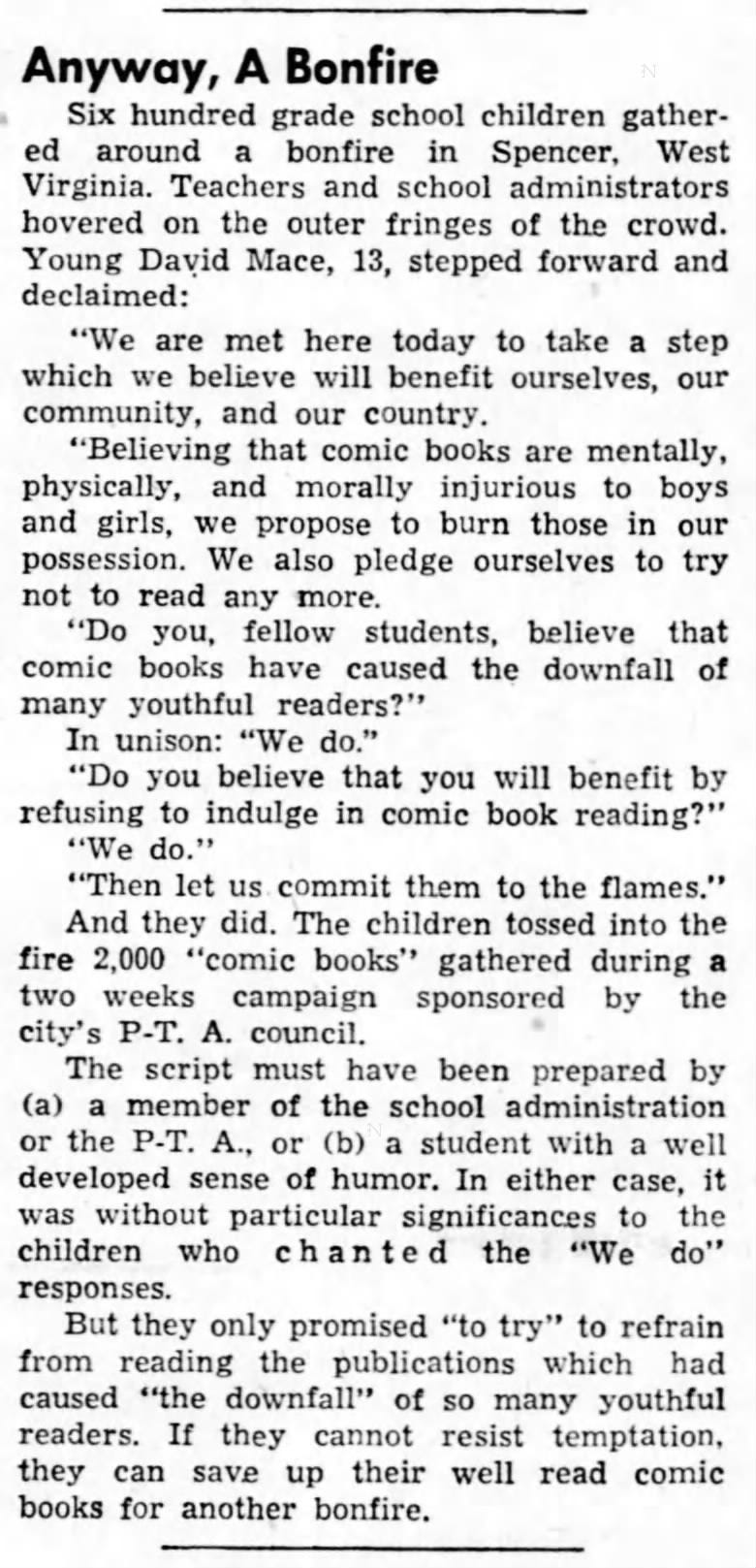

“The first reported comic-book burning took place in November of 1945 in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, a town of eleven thousand located about a hundred miles north of Madison. The children of Saints Peter and Paul School torched 1,567 comic books accumulated during a school-sponsored collection drive, all titles which a Catholic censor had classified as “condemned” (Batman, The Green Hornet, Wonder Woman) or “questionable” (Dick Tracy, Orphan Annie, L’il Abner). Two years later, students at Chicago’s St. Gall’s School burned three thousand comics after a collection drive organized at the impetus of a ten-year-old student.

These incidents at first received little national attention. The fervor for destroying comic books only caught fire when Frederic Wertham brought the issue to the fore in the spring of 1948. Wertham, the German-born director of psychiatry at Queens Hospital, had also founded the Lafargue Clinic, the first mental health clinic in Harlem. Basing his claims on his extensive study of the children and teenagers he treated there, Wertham debuted as an expert on the subject in Collier’s in March 1948 in an interview titled “Horror in the Nursery.” Two months later, his essay “The Comics—Very Funny!” appeared in the Saturday Review of Literature; a condensed version appeared in the widely read Reader’s Digest in August.”

Wertham’s “expertise” was met with some resistance (read the Lapham’s Quarterly article which includes a 14-year-old who wrote a letter opposing Wertham’s views) but the burnings continued. What is significant about the Spencer bonfire is that the story was picked up by the Associated Press, running in newspapers across the country, and therefore, inspiring other events in several towns, spreading comic burnings like… well… wildfire.

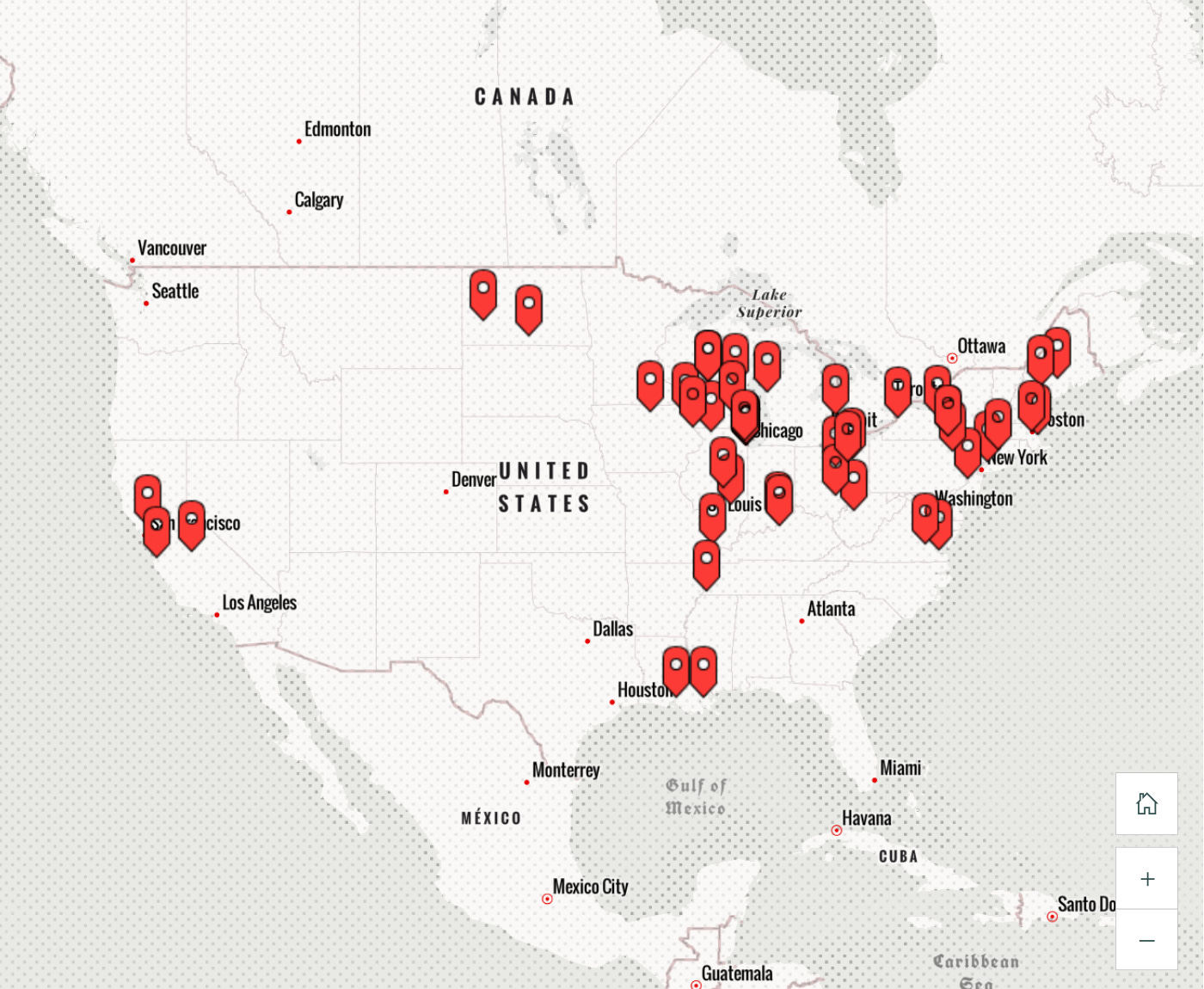

According to the Comic Book Burnings Project, there were fifty other burning events across the United States from 1945 to 1955. The one in Spencer, WV, appears to be the only one to have taken place in the Appalachian region at that time, perhaps because the majority of the population there had much bigger issues with which to contend (e.g. classism, disenfranchisement, systemic poverty).

On the site’s homepage, the irony of the burnings is pointed out in the first sentence of the project’s description:

“1945: The same year the United States defeated the most infamous book burners in modern history, Americans began their own campaign against works deemed to be offensive. While comic books had been subject to criticism even before World War II began, those early critiques focused on the dangers they posed to the individual reader. After the war, comics became a scapegoat for American cultural and social insecurities in the new Cold War world: juvenile delinquency; crime; violence; sexual promiscuity; homosexuality; and more.”

Not only did the U.S. defeat the notorious book burners, but according to Shine’s story, “during World War II, comics made up a quarter of the reading material available at American military exchanges,” not to mention, for better or worse, the FBI had been using comics as a public relations and propaganda tool for years.

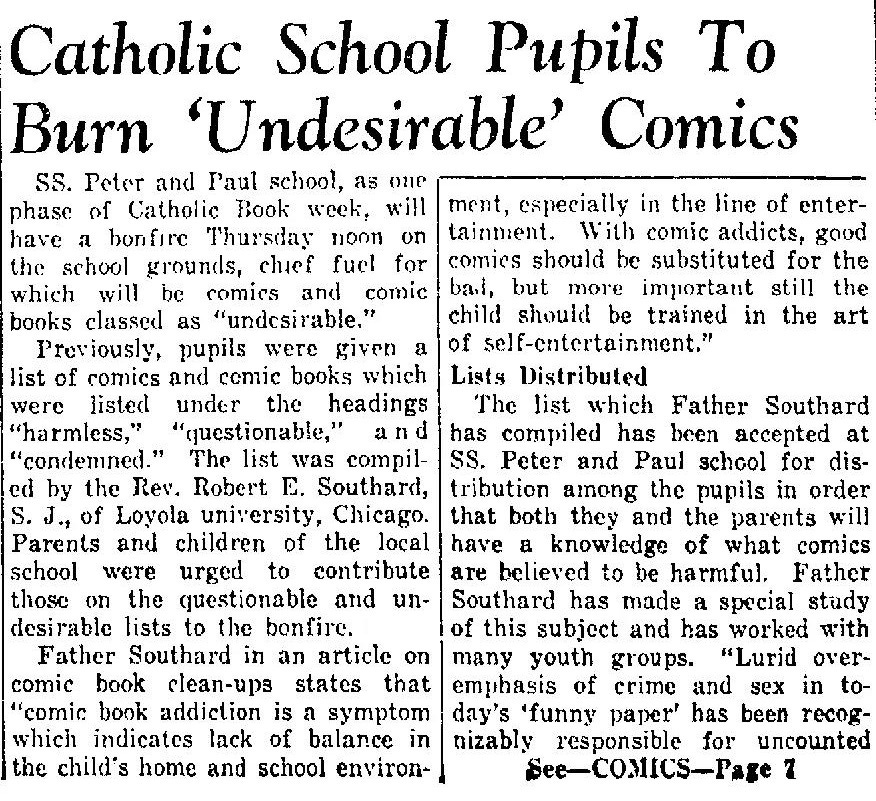

Furthermore, the comic industry itself had felt the public pressure and started self-regulating just a few months before the Spencer burning. The Associated Press reported on July 2, 1948, that “14 comic book publishers had adopted a ‘comics code,’ and had agreed not to publish any comics which feature sadistic torture, glorify crime or foster religious or racial prejudices. It promised a drive to obtain the cooperation of all other comic magazines in the country.” (This Publishers Code adopted by the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers was deemed largely ineffective until the formation of the Comics Code Authority formed in September 1954.)

But the conflagrations persisted until 1955, a year after the new Code was created.

I found an article from three years later where West Virginia’s State Textbook Committee were beginning to choose new math, health, and science textbooks for the state’s elementary schools. The selections had to be ready no later than April 1, 1960. April Fool’s Day. Six of the committee’s members were new employees, all of whom were elementary teachers, and one of whom was Mrs. Mabel Riddel (misspelled as “Riddle” in the story here like in Orlean’s book).

She died in 1990, a week before her 94th birthday, and is buried in Lewisburg, WV.

Orton Jones, attorney and former West Virginia delegate and state senator, published a column in the August 11, 1988, of Spencer’s The Times Record (and republished in the February 9, 2006, edition) where he defended the burning, which he had attended, writing:

“Our sixth grade reading teacher, Mrs. Riddel, recognized that our precious young lives were being eaten away by this terrible sore. We weren’t reading library books. We were reading comic books. We were fast on our way to the illiterate adults we would become.”

He goes on to say Mrs. Riddel “would not sit by and watch us precious little kids become violent unlettered clods with beady strained eyes” and that she “devoted her reading classroom every Friday to Bible study” before, he says, the Bill of Rights “intruded” more on our daily lives.

However, he only brought his “most worn, least valuable comic books” to the bonfire and left the good ones at home. His classmate, Lenzy Reynolds, was inconspicuously reading from his newest comic when Mrs. Riddel asked him if he was going to put it on the fire. “Yes, ma’am,” responded Linzy. “That thing cost him a whole dime,” writes Jones, “and he hadn’t gotten to read half of it.”

Jones writes that he had run into Reynolds a few weeks prior to and “he would still like to have that comic book back.”

“By and large, however, those teachers were probably right. We went back to reading comics as usual and trading them around. But the whole thing took on a new dimension. We now knew we were being corrupted. And that made it all worthwhile.”

A recent trip to Books-a-Million signaled to me that 77 years after the Spencer burning not only are comics doing just fine, but “banned books” themselves apparently are not a bug, but a feature, serving as a reminder to us all that you can defund, dismantle, ban, and burn, but you can’t stop ideas.

Besides, a recent international survey of adult skills revealed that 28 percent of adults in the U.S. aged 16-65 read below the equivalent of a third-grade level. Most comic books today are written at least at an eighth-grade level. Wouldn’t reading something be preferable to reading nothing?

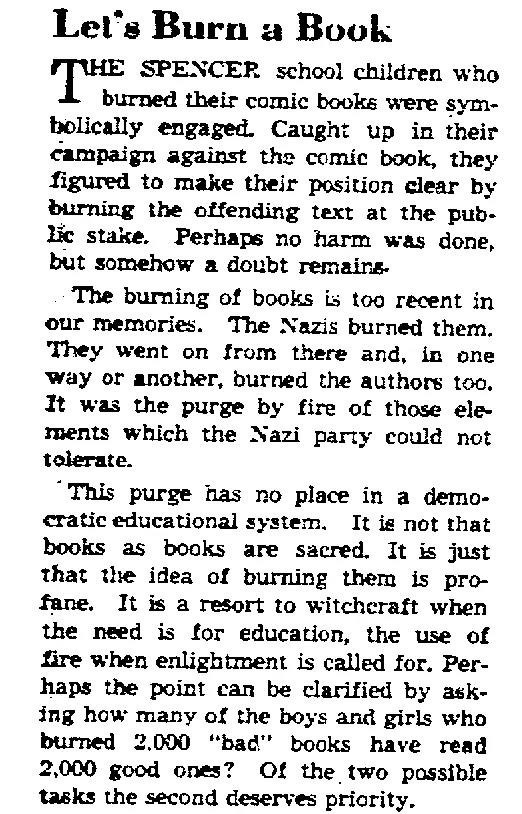

An editorial published in the Charleston Daily Mail, November 1, 1948, days after the burning in Spencer disagrees with Mace, Jones, and Riddel, also noting that the burning of books was something the Nazis had too-recently done, “and, in one way or another, burned the authors too.”

The opinion continues:

“This purge has no place in a democratic educational system. It is not that books as books are sacred. It is just that the idea of burning them is profane. It is a resort to witchcraft when the need is for education, the use of fire when enlightenment is called for. Perhaps the point can be clarified by asking how many of the boys and girls who burned 2,000 ‘bad’ books have read 2,000 ‘good’ ones? Of the two possible tasks the second deserves priority.”