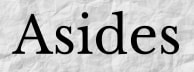

When we first see Pete Seeger in James Mangold’s new Bob Dylan film A Complete Unknown (2024), based on Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties about the events leading up to Dylan’s performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, the popular folk singer and activist is on trial in 1961 after being subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) which accused him of Communist activities. Seeger disputed not only these allegations but those of the “dangers” and “un-American” charges of folk music by asking the judge if he could play his banjo and sing some folk songs in court.

This all really happened. The judge denied Seeger’s request to perform, and the musician was found guilty of contempt of Congress for his 1955 refusal to answer whether he was or had ever been a Communist.

One could argue the folk music boom of the time had gathered momentum partly because of the HUAC hearings giving the artists cultural relevance and cachet. Many Americans felt the hearings were unjust, therefore positioning the artists and activists as heroes from their viewpoint.

For example, the Weavers were invited to perform at Carnegie Hall on Christmas Eve of 1955, the same year Seeger was questioned by Congress, after the group had been included on the entertainment industry blacklist. It could be seen as a gesture of solidarity and support on Carnegie Hall’s behalf, but it’s been said the venue wasn’t aware of their troubles. The Town Hall had refused to book them because they were aware. Nonetheless, the Carnegie Hall show sold out.

An album of the performance was released by Vanguard in 1957 and spawned a reunion album six years later. (Seeger left the group that same year, objecting to the Weavers performing for a cigarette commercial. He filmed the commercial, then quit.) Another final reunion concert was filmed in 1980 and released as the documentary Wasn’t That a Time? (1982), which inspired Christopher Guest’s Oscar-nominated mockumentary A Mighty Wind (2003).

Seeger, the Weavers, Harry Belafonte, Dave Van Ronk, Jean Ritchie, the New Lost City Ramblers, and many more were enjoying some level of success, holding their own for the time being against rock-and-roll, which was losing itself, in part, to payola scandals and the declining quality of Elvis Presley movies. Folk music offered an alternative to the homogenization of mass market music and culture, and by the early 1960s, new folk acts were emerging all over the country, including the Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul & Mary, Joan Baez, Richie Havens, Bob Dylan, and dozens of others.

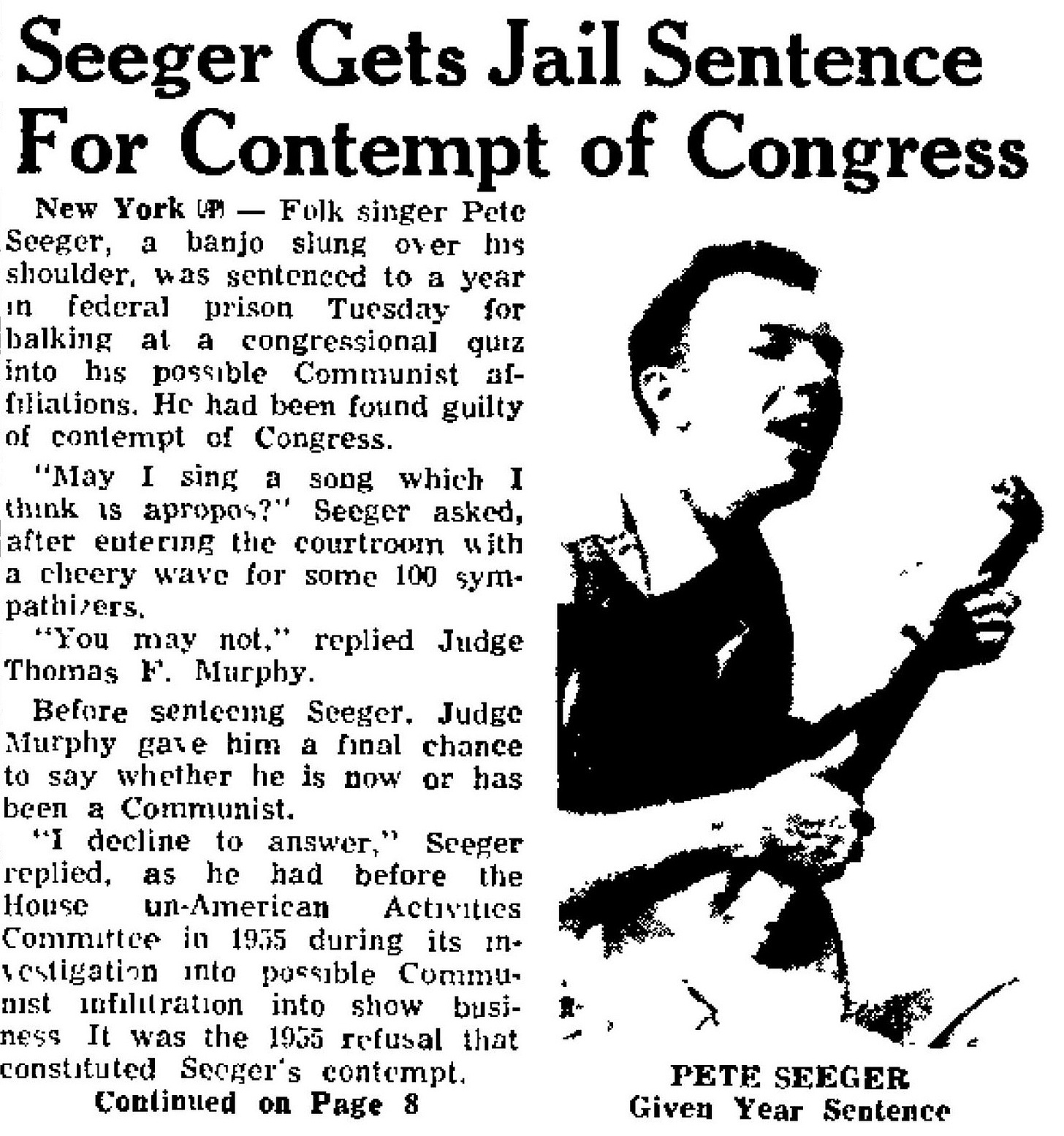

On September 22, 1962, Dylan appeared for the first time at Carnegie Hall, as part of a six-act hootenanny, including Seeger, the New World Singers, the Lilly Brothers (of Clear Creek, WV) & Don Stover, and more. Dylan premiered his song “A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall,” which Seeger said later would outlast any other Dylan song. A month later, President John F. Kennedy warned the Soviet Union over their deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba, and the song would (presciently, coincidentally) gain a resonant boost.

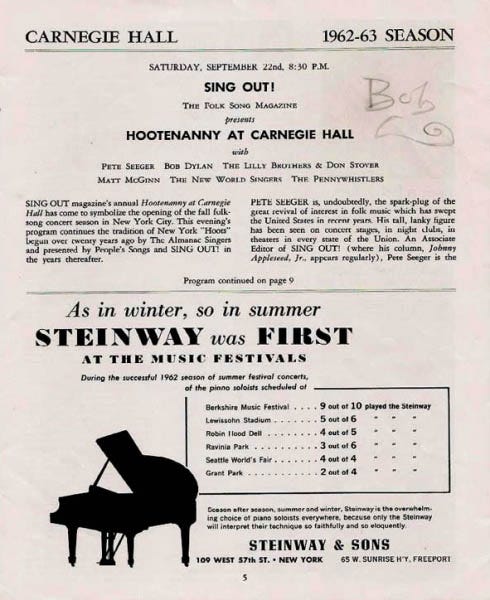

In an article about Seeger published in Geneva, NY’s The Herald the same day as the concert, the artist was quoted as saying:

“Folk music is at its healthiest when people participate. I notice also that you’ll find more awareness of counterpoint and harmony when you have an audience sing along with you today than was the case a few years ago. This is healthy, indeed, for it stems from the pioneer days whence community was made up of good friends and neighbors. It’s this attitude which drives out prejudice, snobbery, and class distinctions, which, in a word, makes us know that America is truly a land of freedom for all.”

A couple of months later, on November 18, 1962, ABC filmed a live performance pilot at Syracuse University and directed by Gil Cates (who would go on to direct many Academy Awards broadcasts). The show Hootenanny was created by Dan Melnick, Vice President of ABC-TV (and who would go on to produce films like Straw Dogs, All That Jazz, Roxanne). It was originally conceived as a half-hour special to feature folk, bluegrass, and comedy acts, but expanded into a thirteen-episode season.

bCates wanted to tape the program at a college campus so as to include the student audience on camera, singing and clapping along with the music. Fred Weintraub, owner of The Bitter End, a folk music club in New York's Greenwich Village, served as talent coordinator.

Writer Jean Shepherd (1983’s A Christmas Story film was based on his book In God We Trust: All Others Must Pay Cash) was the host of the show for the pilot but the producer replaced him with Jack Linkletter before it aired.

Shepherd did, however, write a piece for the first edition of Hootenanny magazine (January 1964):

“If Joan Baez were a short fat girl, with blonde hair in an up-sweep, I wonder if she would be accepted by the Folk addicts as a True Folk? Or can you picture Bob Dylan wearing thick, horn-rimmed glasses, and pimples? Would he be accepted as a Messenger of the True Gospel? Of course not. It's all part of the scene, you see. You have to look exactly like what you claim you are. As Theda Bara was THE Vamp, and then a few years later Clara Row was THE Flapper, now Joan Baez is THE Folk Singer. Definitive.”

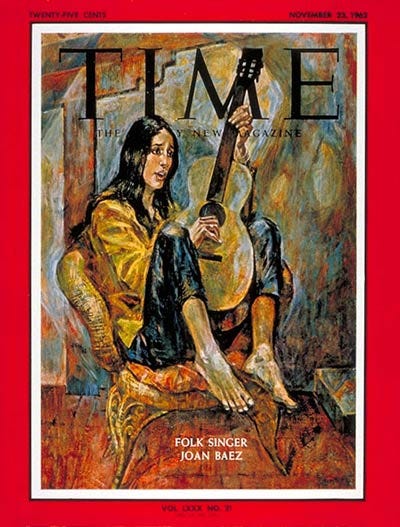

The same month the pilot was being taped, Joan Baez was on the cover of Time magazine, another example of folk music’s popularity at the time.

The television crew shot two shows at six different universities across the country, not including the pilot taped at Syracuse. Hootenanny premiered on April 6, 1963, with the first season continuing until June 29, 1963. (One of the groups featured on the first and last episodes was the Limeliters, who recorded the infectious and popular “Things Go Better With Coke” jingle that same year.)

A review of the show in the New York Times, while positive, offset the network’s “belated recognition of interest in folk singing” with the concerns of Pete Seeger’s absence from “all network shows of folk singers.” They reason if Seeger could be heard live and on recordings, why should he remain blacklisted on television?

Eighteen days after the show’s premiere, Dylan was in the studio recording the final tracks for his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, which was released on May 27, 1963.

Fifteen days before the album’s release, Dylan was to perform on CBS’s The Ed Sullivan Show. He decided to perform “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” a song mocking the conservative John Birch Society and its Red Scare paranoia. Dylan auditioned the song for Sullivan who seemed to have no problem with it. However, during the show’s dress rehearsal, an executive from the CBS Standards and Practices department decided Dylan could not perform the song, deeming it too controversial. When the show’s producer informed Dylan, the singer responded by saying, “No, this is what I want to do. If I can’t play my song, I’d rather not appear on the show.”

So, he walked off the set of the nation’s highest-rated variety show.

The story received media attention and helped cement Dylan’s reputation as an uncompromising artist. However, the song didn’t make Freewheelin’s final album sequence. Dylan had presumably lost that battle with Columbia Records a month or so prior, when he recorded those four new tracks to finish the album.

Meanwhile, Dylan, Baez, Tom Paxton, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and several other acts were boycotting Hootenanny because they claimed Seeger was being passed over for “alleged political reasons.” Ironically, Seeger along with Woody Guthrie helped to popularize the word “hootenanny” which they would call a rent party where they and their many of their peers would perform. (Rent parties were often held to help collectively raise rent for tenants.) The term would carry over to promote folk music concerts with several acts, like the one Seeger and Dylan played at Carnegie Hall.

Seeger, however, encouraged his fellow artists not to boycott the show, but to accept the invitations, perform, and promote the folk genre itself.

ABC aired another season of Hootenanny from September 21, 1963, to April 25, 1964, this time consisting of thirty episodes, more than doubling the number of colleges and episodes of the first season.

[For local readers, one of the colleges visited was then-named Salem College in Salem, WV, because the CEO of one of the sponsors went to school there. Two episodes were taped in Salem. Performers included the Geezinslaw Brothers, the New Christy Minstrels, Flatt & Scruggs, Pat Harrington Jr. (who later played Schneider on One Day at a Time) and popular husband-and-wife comedy team Stiller & Meara (Jerry Stiller later of Seinfeld, Anne Meara later of Rhoda, both later Ben Stiller’s parents).]

Weeks before the season ended, the Beatles played The Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964, to an audience of screaming fans.

The Liverpool quartet was dominating the charts, rock was renewed, and more British were coming.

ABC saw another boom exploding and decided to change course.

Hootenanny’s viewership was down, and the network announced on June 8, 1964, that the show was canceled.

Furthermore, Gene Clark left the New Christy Minstrels and helped form the Byrds. Cass Elliot left the Big 3, John Phillips left the Journeymen, and the two of them went to be part of the Mamas & the Papas. John Sebastian left the Even Dozen Jug Band and helped create the Lovin’ Spoonful. All of these folk groups they left behind had appeared on the show’s second season.

ABC quickly replaced Hootenanny with Shindig!, which premiered on September 16, 1964, and featured Sam Cooke, the Everly Brothers, and the Righteous Brothers.

Despite all of this, Dylan’s star was still rising. Columbia had released The Times They Are A-Changin’ on February 10, 1964, the day after the Beatles were on The Ed Sullivan Show. He recorded the entirety of his fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, on June 9, 1964, the day after ABC’s announcement of Hootenanny’s cancellation.

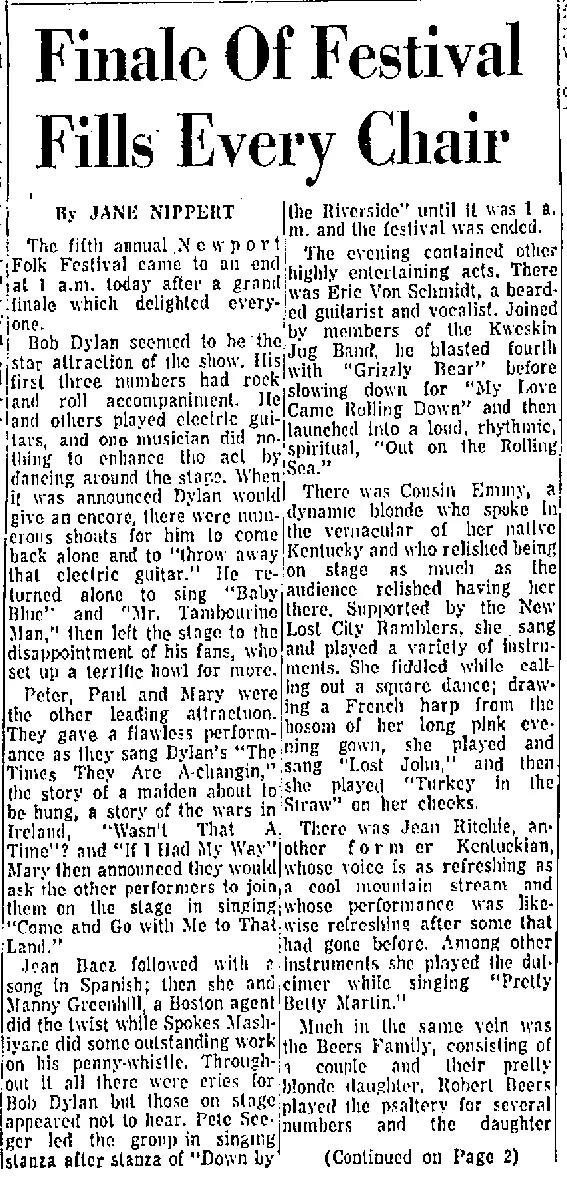

He performed songs from that album at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1964. Johnny Cash performed Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” at the same festival, saying that “we've been doing it on our shows all over the country, trying to tell the folks about Bob, that we think he's the best songwriter of the age since Pete Seeger.”

In his episode on Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” from his invaluable podcast A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs, Andrew Hickey makes the case that despite the boycott and traditional folk fans not interested in “watered-down” commercial folk acts, Hootenanny existed and therefore gave folk artists a large audience they wouldn’t have otherwise. Even the commercialized folk acts were important to a thriving scene, and they—and therefore, the genre writ large—were losing popularity. audience numbers, and “commercial relevance” because of rock’s comeback and Shindig! now in the place of Hootenanny on one of the three major broadcasting networks. Seeger knew this and that’s why he encouraged others to do the show

Hickey continues:

“And so many of the old guard in the folk movement weren’t wary of electric guitars *as instruments*, but they were wary of anything that looked like someone taking sides with the new pop music rather than the old folk music.”

Hickey goes on to talk more about Dylan’s divisive Newport performance, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, an altercation between Alan Lomax and Albert Grossman, the sudden appearance of Al Kooper, Pete Seeger’s wrestling with his own feelings about the performance, and the oft-repeated most-likely-apocryphal legend of Seeger “grabbing an axe” as if planning to hack the electrical cord.

Dylan recorded “Like a Rolling Stone” in early June 1965 and Columbia Records released it on July 20, 1965, five days before Dylan performed it, “Maggie’s Farm,” and “Phantom Engineer” (reworked and rerecorded four days later as “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”) before a divided audience at the Newport Folk Festival—some booed and possibly threw things, and some of that hostility could be, as Hickey and others have pointed out, a sound quality issue—sounding great to the cheap seats, terrible in the front. (For the record, Newport must not have necessarily despised rock outright, Chuck Berry performed at the festival the following year. Ironically, ABC had canceled Shindig! by then.)

Nonetheless, “Like a Rolling Stone” reached number 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, and in 2004, Rolling Stone placed it at number one on its list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.”

But while A Complete Unknown understandably ignores some of these events (it would take something like a broad-scope documentary to incorporate all of the relevant elements), the Hootenanny factor and the folk scene’s diminishing popularity due to mass media decisions and rock’s reinvigoration could be another reason emotions were running high among the folk purists in attendance: it was another battle lost.

To frame it in Civil War terms, if Dylan’s performance at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965 was the Gettysburg of the era’s theoretical folk vs. rock culture war, then the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and the cancellation of Hootenanny a year prior may have been its Antietam.